Common Wealth VS. Neoliberalism: A comparison between Chinese and Western Capitalism — a historical perspective

Amidst the global tapestry of conflicts, China's ascent takes center stage, illuminating the deepening divide between Western and Eastern civilizations. Each faction fervently champions the superiority of its own political systems, perceiving the opposing side as fated to be eclipsed in the sweeping currents of history.

In the center of the conflict lies the battle between the capitalist ideology, spearheaded by the United States, and the socialist ethos, embodied by China. Over the past half-century, these two civilizations have been shaped by two dominant ideas: the Western emphasis on neoliberalism and China's pursuit of common prosperity.

This article won't delve into discussions about the superiority of systems; it simply offers a historical perspective. The goal is to foster mutual understanding between two civilizations, to illuminate that the choices in their respective systems are deeply rooted in history. It seeks to enhance empathy because, in the end, regardless of civilization, humanity is united in the pursuit of a better life.

The Roots of Civilizations

Throughout history, Western civilization has displayed a pronounced inclination towards individualism, prioritizing personal freedom over collective interests. Civil society, which constitutes atomic individuals, is always in conflict with the government. Individual rights are considered sacred and absolute; individuals cannot and should not relinquish their rights to the collective or the state. When freedom and social equality come into conflict, individual freedom takes precedence. This ingrained individualism leads to a tendency in Western history to categorize things in a starkly binary manner—either with me or against me. This zero-sum game thinking, where differences must be eliminated, has led to numerous religious and ethnic conflicts in Western history.

In the annals of Chinese history, the emphasis on individual freedom takes a backseat to a stronger focus on national and societal obligations, placing paramount importance on the welfare of the collective. If individual rights and the interests of society are in conflict, individuals must sacrifice some of their rights to achieve the maximization of the welfare of the whole society, thus it seeks to prioritize equality over personal interest.

"Do not be concerned about the fewness of people; be concerned about the unequal distribution of wealth." – Confucious (不患寡而患不均 )

Moreover, civil society is traditionally aligned with the government, marked by a longstanding history of centralization, wherein the state has played a regulatory role throughout history. In contrast to Western civilization, China values harmony, embracing the coexistence of yin and yang. The emphasis is on seeking the middle ground — finding commonalities while accommodating differences,and prioritizing collective interests over individual distinctions (求同存异).

China's traditional values have persisted to this day and continue to exert a significant influence. Unlike the frequent intense upheaval witnessed in Western history, which led to the overthrowing of past values, China's traditional values, promoted 4000 years ago, still hold relevance today. President Xi's Chinese Dream revolves around the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, which entails a resurgence of traditional culture.

In comparison, Western notions of freedom, democracy, and human rights evolved relatively recently in modern history. A U.S. president asserting a revival of medieval values finding favor in today's political landscape is just plain strange.

Tracing the Roots of Capitalism

While capitalism sprouted in both Western and China almost simultaneously within the framework of feudal societies, the distinct historical contexts set them apart profoundly. In the West, the budding capitalism evolved into a fully-fledged system, whereas in China, it took a different trajectory.

China's economic policies exhibit remarkable consistency in certain features over centuries. The government has maintained a long tradition of centralization accompanied by government intervention. The powerful state undertook large-scale construction projects over 2000 years ago, a time when Europe was scattered with multiple power centers. The government acted as a parent, guiding the market toward socially desirable outcomes without stifling its dynamic force.

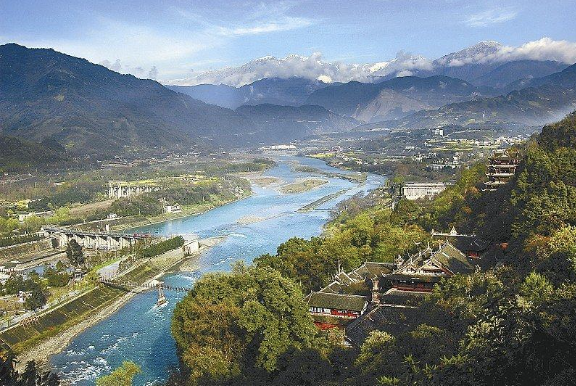

Figure 1: Dujiangyan Irrigation System

In the Spring and Autumn Period, 20 BCE to 480 BCE, the government implemented grain reserve regulations for price stability, this included purchasing during abundance and releasing in scarcity. Centralized authority supported major hydraulic projects, such as the Dujiangyan irrigation in the state of Wei.

In Medieval Europe, characterized by small and weak political states, no single and centralized power agency controlled a well-defined territory. Consequently, most social relationships were highly localized, revolving around one or more cell-like communities. Unlike China, the government wasn't interested in taking away large quantities of essential goods. Instead, they focused on taxing these goods. In exchange for taxes, the state provided the basic structure for social order.

Furthermore, agriculture served as a cornerstone in the economy of feudal society, enduring for centuries. The Chinese agricultural economy was characterized by a unique trait of self-sufficiency, whereby trade and exchange was considered relatively unnecessary. Throughout ancient Chinese history, a longstanding policy, encapsulated in the phrase "zhong nong yi shang(重农抑商)", emphasized the advocacy of agriculture while suppressing commerce.

It's crucial to emphasize that the term "suppression" doesn't imply governmental intent to eradicate trading activities, it simply means the preference for agriculture over commerce, since farmers were the bedrock of society. Dissatisfaction with farmers could pose a serious threat to an emperor, as many dynasties had ended in a farmers’ rebellion.

Feudal Europe also placed importance on agriculture, but the difference lay in the fact that the government did not downplay the role of commerce while advocating for it. Feudal monarchs, to combat local separatism, needed to enhance their economic power by supporting the development of capitalist industry and commerce. The political fragmentation in most Western countries, characterized by limited government intervention, created a relatively permissive environment for the emergence and development of capitalism.

Whereas in China, the commercial economy reached an unprecedented height during the Ming dynasty. Despite its predominantly agrarian nature, there was rapid growth in commodity trade. Rural market trade prospered significantly, with active regional commodity circulation. Private overseas trade thrived, and the use of silver in the monetary system further stimulated commodity growth.

The trait of capitalism seems to sprout.

Commerce = Capitalism?

Undoubtedly, commerce boasts a rich historical legacy in China. Those interested in exploring this history can draw upon a plethora of evidence to showcase the prosperity of ancient Chinese trade. However, regardless of how advanced commerce became, it consistently remained tightly controlled, regulated, and suppressed by imperial states.

State-owned commerce was essentially used by the imperial state to serve political ends. Non-state-owned commercial activities in society, adhering to the enduring policy of suppressing commerce for millennia, never experienced development free from authoritarian rule, offering no fertile ground for the growth of capitalism. While commerce is a historical prerequisite for capitalism, it alone is not a sufficient condition for its emergence.

Thus, China did not actually go through a capitalist era; it skipped over it. Instead of calling it the sprouting of capitalism, it is more accurate to label it the emergence of modernization.

Capitalism in the West

The decline of feudalism marked the advent of the Renaissance—a cultural and intellectual revival that created an environment favorable to economic innovation. This period set the stage for the transition to capitalism. As capitalism evolved, charter companies like the Dutch East India Company and the English East India Company emerged, gaining royal charter support, marking the start of a close relationship between capitalism and the state.

Capitalism gained traction in the West through the subsequent Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries. Technological advancements and the rise of a burgeoning merchant class transformed agrarian economies into industrialized powerhouses.

The Emergence of Neoliberalism

The 20th century witnessed significant shifts in economic thought. The Keynesian revolution, spurred by economist John Maynard Keynes, advocated for government intervention to manage economic downturns through fiscal and monetary policies. This approach gained prominence in the aftermath of the Great Depression and continued to influence Western economic policies for several decades.

The rise of stagflation in the 1970s provided an opportunity for the rise of neoliberalism. From the 1980s until the outbreak of the international financial crisis in 2008, neoliberalism experienced a period of rapid development. In simple terms, neoliberalism advocates the principles of "marketization, privatization, liberalization, and global integration."

The essence of neoliberalism is deeply ingrained in the roots of Western civilization, particularly in its emphasis on individualism. The relentless pursuit of absolute individual freedom has led to a steadfast opposition to government intervention. Central to this ideology is the belief in the paramount importance of private property over public property, seen as crucial in ensuring individual freedom. In a society built on private ownership, while individual incomes may be unequal, the opportunities to accumulate wealth are intended to be made equal.

Neoliberalism places a higher value on individual freedom than on social equality, a viewpoint that, to some degree, echoes capitalism's tendency to suppress demands for equality from the lower and middle classes.

Modern China

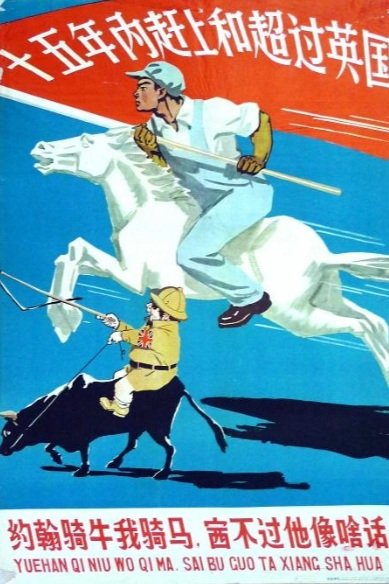

Figure 2: The Great Leap Forward Propaganda Poster

(It depicts a Chinese man on horseback racing past a British soldier. The caption reads, “China should surpass Britian in 15 years”.)

The Qing Dynasty and the century thereafter witnessed a period that the Chinese people would refer to as the Century of Humiliation.

After the establishment of New China, the initial period witnessed Chairman Mao's initiatives, including the People's Communes, the Great Leap Forward, and a radical push towards communism, along with an era marked by intense ideological struggles.

The argument about whether China is a capitalist state began in the 80s, when Deng Xiaoping started Reform and Opening-up, unleashing the era of modernization.

The Era of Pragmatism

The reformers initiated their efforts in the 80s, gaining momentum in the 90s. The collapse of the Soviet Union served as a decisive refutation of the Soviet economic model and removed substantial barriers for China's economic reforms.

In his 1992 southern tour, Deng advocated for a pragmatic approach to economic development. He emphasized the significance of assessing policies based on their tangible outcomes rather than rigidly adhering to ideological disputes, whether socialist or capitalist.

"Regardless of whether it's a black cat or a white cat, as long as it catches mice, it's a good cat." -Deng

While focusing on stimulating economic growth may lead to temporary challenges such as wealth disparities, it is essential to allow certain individuals to accumulate wealth first. Addressing inequality concerns can be prioritized at a later stage. If market forces can help enlarge the cake in the short term, then harnessing market forces becomes even more crucial.

In 1992, Deng Xiaoping made his second visit to Shenzhen, the first special economic zone of the country, at the age of 88.

Figure 3: Deng’s Southern Tour

A De Facto Capitalism?

From the late 1990s to the early 2010s, China continued its Reform and Opening-up policies, promoting a market economy with many pro-capital measures. During this time, ideological disputes took a back seat, often accompanied by frequent but obscure official theoretical justifications asserting the continued alignment of current policies with socialist concepts, yet these explanations didn't capture much public attention.

This shift gave rise to the perception that China had embraced capitalism, leading to a common saying that China was "signaling right while driving left". In Western academic circles, both left and right-wing economists have grown accustomed to characterizing China's ruling party as pro-capital, with some arguing that it is leaning towards state capitalism.

Thus, when the common prosperity policy was again brought up in recent years, the immediate impression to many people is that China planned to drive back to the period of Mao, where absolute egalitarianism is advocated, the state loots from the rich to rescue the less fortunate.

The Common Prosperity

So, how should we understand the concept of common prosperity? The idea of " harmony" has been the ideal of the Chinese people since ancient times. There has always been a deep-seated desire for fairness, aspiring for everyone to prosper together.

In the early stages of economic development, China's economic policies were positioned on the right. At that time, the focus was on prioritizing market efficiency over equality. Adequate economic development is a prerequisite for fairness.The idea was to let some people become rich first, and then engage in discussions about fairness.

As the economic cake continues to grow, China's political and economic policies are gradually shifting to the left. Anti-corruption efforts, salary reductions in the financial sector, and the long-term downplaying of real estate are all steps toward social fairness.

Figure 4: Occupation of Wall Street in 2011

This sense of correction—after a shift to the right, there will be a turn to the left, prioritizing social fairness—is a concept unique to socialism. Capitalism in neoliberalist country seems to miss out on this sense; while thousands of irate ordinary folks occupy Wall Street in 2011, the elite seem to be enjoying the spectacle from their backyard, smiling as if they're watching a comedy show.

Neoliberalism —The Rich White Man’s Economy

The scenes in Wall Street are largely a result of the inequality brought about by neoliberalism. Overtime, neoliberalism has led to the hollowing out of manufacturing, and financialization, resulting in the concentration of labor in the financial sector and the disappearance of manufacturing jobs.

Around the 1980s, two neoliberalist leaders came to power—Margaret Thatcher as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Ronald Reagan as the President of the United States. Both advocated for tax cuts, welfare reductions, and privatization. While they achieved some short-term results, it led to a further widening of the wealth gap.

Figure 5: President Reagan during an Oval Office meeting and working visit with Prime Minister Thatcher of the United Kingdom.

Unlike socialism, neoliberal countries lack the concept of correction. The Social Darwinism inherent in the capitalist spirit implies that individuals in poverty are believed to be in that situation due to their own lower capabilities and laziness. The government has no responsibility to care for individuals, each person is expected to bear the consequences for themselves.

The interest of ordinary people continued to be overlooked, take the United States as an example—only large capital has the ability to lobby the government to influence policies, and the interests of the ordinary citizens have consistently been underrepresented, leading to the later election of Trump.

Moreover, as previously noted, Western civilization tends to eradicate anything divergent. When the neoliberal policy yielded successful results in the United States in 80s, boosting its stagflation economy, the Western world at that time began to consider neoliberalism as a panacea . Neoliberalism, under the promotion of the West, flourished in Latin America, Asia, and other regions, despite leading to undesirable outcomes.

Figure 6: The Washington Consensus

The efforts demonstrated in the proposal of the Washington Consensus included a set of ten reform measures for the Latin American region. It brought short-term prosperity to Latin America, but caused more severe and widespread social problems in the long-term.

The radical and blind relaxation of financial regulations, coupled with an open trade environment in Asian countries after embracing neoliberalism, exposed them to the malicious speculation of international capital. This, to some extent, contributed to the Asian financial crisis in 1997.

Overall, when neoliberalism is exported to other countries, it fails to achieve the expected outcomes. Internally, in Western nations, it leads to deepening inequality without a corrective mechanism. The will of ordinary people remains underrepresented, and its perspective continues to be manipulated by the elite media in the foreseeable future.

In The End

This article highlighted the key points in history, not to argue the superiority of any system. Rather, through the historical narrative, the aim is to convey that the choice of a system has deep historical roots, extending beyond individual decisions. In different historical epochs, every civilization has undergone various political transformations—whether under the ideology of capitalism or socialism, some policy thrived, while others faltered. These brief moments of development and setbacks, in the grand river of history, are but fleeting.

Sources

Valéry, P., & Gilbert, S. (1970). Analects.

Cainey, A. & Prange, C. (2023) Xiconomics : What China’s Dual Circulation Strategy Means for Global Business / Andrew Cainey and Christiane Prange. Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Agenda Publishing Limited.

Zhang, G. (1995). A Comparative Study on the Germination of Capitalism in China and the West. Journal of Xuchang Teachers College, Social Science Edition, 14(2), 56-60.

Nolan, P. (2020) Finance and the Real Economy: China and the West since the Asian Financial Crisis. [Online]. Milton: Taylor and Francis.

Baechler, J., Hall, J. A., & Mann, M. (Eds.). (1988). Europe and the Rise of Capitalism (1st ed.). Blackwell.

Loewe, M. & Shaughnessy, E. L. (1999) The Cambridge history of ancient China : from the origins of civilization to 221 B.C. / edited by Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zhu, S., (1982). Ancient Chinese History, Volume 2. Fujian People's Publishing House. Retrieved from University of Michigan, Digitized 20 Mar 2009

Cayla, D. (2023) The decline and fall of neoliberalism : rebuilding the economy in an age of crises / David Cayla. London: Routledge.

Zhang, N. (2021). A Study on the New Changes of Neoliberalism in the Post-Financial Crisis Era. (PhD dissertation, Foreign Marxism Research, Central Party School of the Communist Party of China, Beijing).

Deng Xiaoping Speeches Editorial Board. (2018). Selected Speeches of Deng Xiaoping. Hongqi Publishing House. ISBN 7505144715, 9787505144712.

https://www.tripadvisor.co.uk/Attraction_Review-g681034-d319640-Reviews-Dujiangyan_Irrigation_System-Dujiangyan_Sichuan.html

https://www.npr.org/sections/pictureshow/2012/11/16/164785930/the-art-of-chinese-propaganda

http://www.chinatoday.com.cn/english/economy/2017-01/05/content_733476.htm

Occupy Wall Street: An experiment in consensus-building | CNN

https://simple.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:President_Ronald_Reagan_During_An_Oval_Office_Meeting_and_Working_Visit_of_Prime_Minister_Thatcher_of_The_United_Kingdom.jpg

https://twitter.com/PIIE/status/1461750874959712267/photo/1

Note that opinions expressed in the article above do not necessarily represent the overall stance of Asiatic Affairs, Students' Union UCL or University College London. If you have read something you would like to respond to, please get in touch with uclasiaticaffairs@gmail.com.

Want to write for us? Don’t worry about experience - we are always looking for writers interested in Asiatic affairs. Submit your ideas at https://forms.gle/Bujy1CV1mXSfRjdQA and we’ll get in touch.